On March 2, 1932, the son of aviation hero Charles A. Lindbergh was discovered missing from his crib. Only a few meager clues, including a homemade ladder, were left behind, and because forensic science was not a technique used in crime-solving just yet, law enforcement had little to go on in finding the missing child and his kidnapper.

However, this kidnapping — dubbed “the crime of the century” at the time — and its subsequent investigation opened the doors to forensics in solving crimes. U.S. Forest Products Lab scientist, Arthur Koehler, used microscopic techniques to identify and pin the specific wood used on the homemade ladder to Bruno Hauptmann. Koehler’s contributions to the investigation changed the course of crime-solving history.

What Happened to the Lindbergh Baby?

Charles Lindbergh and his family gained national attention when the hero made his solo flight across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis. They were a well-beloved family of the nation, and everyone was demanding retribution when their 20-month old son was kidnapped on March 1, 1932, from the second-floor nursery of their Hopewell, New Jersey, home.

Unfortunately, there were no eyewitnesses, and the only clues left behind were muddy footprints, a homemade ladder, a chisel, and a poorly written ransom note. In an attempt to save the Lindbergh baby, the $50,000 ransom was paid. In exchange, the search party was given a letter saying the child could be found on a boat near Martha’s Vineyard Island. However, this boat did not exist, and on March 12, 1932, the body of Charles Jr. was discovered in the woods about a mile from his parents’ home. It was determined that the child died by asphyxiation or blunt-force head trauma the night of the kidnapping.

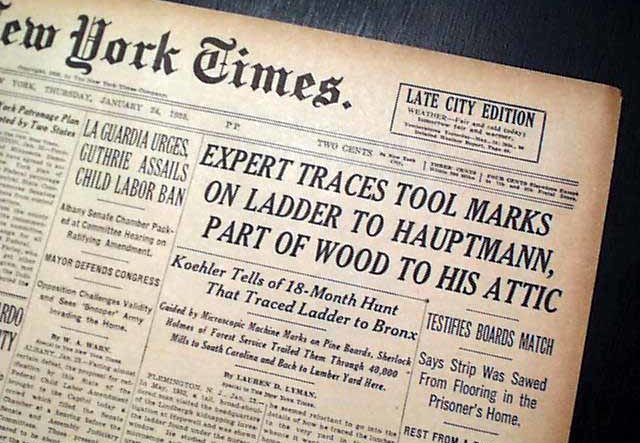

Police attempted to trace the bills used in the ransom to find the kidnapper, but they could only trace the notes to the Bronx. At this point, they turned to wood expert Arthur Koehler to examine the homemade ladder found at the crime scene.

How Wood Forensics Sent the Murderer to the Electric Chair

Almost a year after the kidnapping, Koehler was asked by the head of the U.S. Forest Service to perform an in-depth examination of the ladder. Inside the Forest Products Laboratory, Koehler used the highest-quality equipment to inspect the wood composing the ladder.

From his microscopic examinations, the scientist found the ladder was made of North Carolina pine, Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, and birch. He also discovered that some of the rails on the ladder had distinctive marks from a planing machine that had a defect on its cutters.

Koehler requested planed wood samples from mills across the country. From these samples, he determined the wood came from Dorn Lumber in McCormick, South Carolina. The wood was sold from this lumber yard to National Lumber and Mill Work Company in the Bronx. This is where the Lindbergh kidnapper bought the wood for the homemade ladder. Unfortunately, the company did not have any sales records.

Undeterred, Koehler returned to the lab to continue his investigation of the ladder. During this time, a man was arrested because he had one of the bills from the ransom in his possession. This man was Bruno Hauptmann, a carpenter of German descent.

When investigators searched Hauptmann’s home, they discovered a board missing in his attic. Koehler inspected the board and noted that the wood matched the piece of fir used to complete the homemade ladder. He then compared the holes found in the fir part of the ladder to the holes in the joist of the attic. The holes aligned, connecting Hauptmann to the homemade ladder.

Based on the evidence found in Koehler’s investigation and the ransom money discovered in Hauptmann’s house, Hauptmann was convicted of kidnapping and killing Charles Lindbergh, Jr. on February 13, 1935. He was executed in an electric chair on April 3 of that year.

The Role of Forensics in Solving Crimes

Koehler’s work in the Lindbergh investigation is an excellent example of the objectiveness of science in crime-solving. And it’s thanks to Koehler and scientists like him that the criminal investigation world recognizes how critical microscopes are in gathering trace evidence that can make or break a case.

With so many different types of specimens to examine, a variety of microscopes is needed to allow proper lighting, magnification, and contrast techniques. Often, forensic scientists start with stereo or light microscopes and may then use an electron microscope if they need even higher magnification.

For all your forensic microscopy needs, trust UNITRON. We have everything from stereomicroscopes and digital inspection microscopes with monitors (from UNITRON and ASH Technologies) to microscope replacement parts. Contact us today for a quote!

*Featured image excerpted from https://www.rarenewspapers.com/view/674756.